Why is Opioid Overuse App a necessary?

What is the Opioid Epidemic?

The opioid crisis started in the late 90s with the surge in prescriptions of opioid medicines. This led to widespread usage of both prescription and non-prescription opioids. Starting around 2010, we began to detect a rise in the number of deaths linked to heroin as well. Of recent years, with the growth in illicitly made fentanyl, fatality rates have risen. Drug overdose is currently the biggest cause of unintentional mortality in the United States. Among them, roughly 75,000 fatalities were linked to opioids, and largely synthetic opioids like fentanyl. With widespread use of smartphones in the world, it would be highly useful for an opioid overuse app to help people.

At least 130 people die every day in the United States from an opioid overdose, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2017, a record year, two-thirds of the 72,000 drug overdose deaths were from opioids. And preliminary predictions show the numbers may be considerably higher for 2018.

Measures, such as cutting back on opioid prescriptions, extending access to addiction treatment and expanded distribution of the opioid overdose antidote naloxone. Commonly known as Narcan; lately have been taken to fight the issue but have had little effect thus far.

Failing to have an answer is costing the U.S. lots. The CDC estimates that the entire economic impact of prescription opioid abuse in the United States is $78.5 billion a year. Including the expenditures of health care, lost productivity, addiction treatment and criminal justice involvement.

The missing connection between overdose and antidote

At large dosages opioids, particularly fentanyl, causes fast stoppage of breathing, respiratory failure and death. The physiologic sequence through which people usually succumb from an unintentional opioid overdose. Yet most times death may be averted with early identification and timely intervention. If naloxone is provided in time, because it swiftly restores normal respiration to a person. Whose breathing has slowed or stopped as a result of an opiate overdose.

Unfortunately, many who overdose are helpless to ask for aid in an emergency and so fail to ever obtain the lifesaving opiate antidote naloxone.

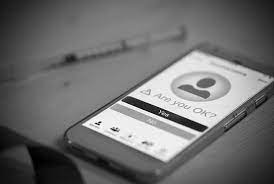

Funded by the UW Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute and the National Science Foundation. The app is a contactless system that converts a smartphone into a short-range active sonar. Using frequency shifts to identify respiratory depression, apnea and gross motor movements associated with acute opioid toxicity.

The team is presently filing for FDA clearance, and they expect the app will be on the market in approximately eight months. Or sooner if they achieve fast track priority approval by the FDA, said Gollakota. The researchers have ambitions to commercialize this technology through a UW spinout called Sound Life Sciences. And are presently working with naloxone businesses. Insurance companies and the local communities that are extensively tackling the opioid issue to make this happen. So far, they believe they have had a very good reaction from several potential stakeholders.

While this software might be used for various kinds of opioid usage, the team notes that for now they have only tested it on illicit injectable opioid use because deaths from such overdoses are the most prevalent.

How it works, in simplest terms

During an overdose, a person breathes slowly or ceases breathing completely. Second Chance detects a person’s breathing pattern by delivering inaudible sound waves from the phone to a person’s chest. And then measuring the way the sound waves return to the phone. If the app detects diminished or absent respiration, it sends an alarm urging the individual to engage with it. If the user fails to interact with the app, Second Chance will instantly alert emergency services or a trusted friend or family member who has access to and can deliver naloxone.

Gollakota said the user may either select they wish to be linked to 911 or input a phone number of a person who has access to naxolone. If a suspected overdose happens. They will receive a text alert and be able to apply the naxolone in a timely way.

“This is a horrible situation that happens, when they have a loved one who dies when they are in the same house. People who are there and might have maybe helped,” said Sunshine. “And that also happens with folks who may be on chronic opioids and fall asleep and virtually never wake up and have a companion in the bed. These are incredibly catastrophic occurrences that do happen, and this might potentially minimize the chance of that happening.”

He added: “There’s two known things: The therapy for it; it’s all known. It’s just connecting the two in a timely method that is needed, and that’s the missing link that this tech is aiming to solve,” said Sunshine.

How Opioid overdose App works

The UW researchers say the app’s algorithm successfully detects overdose-related symptoms approximately 90 percent of the time and can track someone’s respiration from up to 3 feet away.

To acquire access to real-world data to create and test the algorithm, the UW researchers teamed with the Insite supervised injection facility in Vancouver, Canada. Insite is the first legal supervised consumption site in North America. As part of the trial, volunteers at Insite wore sensors on their chests that track respiration rates.

The researchers also sought to make sure the program could detect true overdose episodes, because they occur seldom at Insite. The researchers collaborated with anesthesiology staff in the operating room at UW Medical Center to “simulate” overdoses. Allowing the app to monitor individuals and identify when they cease breathing.

“When patients have anesthesia, they encounter much of the same physiology that people experience when they’re suffering an overdose,” said Sunshine. “Nothing occurs when individuals have this episode in the operating room. Since they’re receiving oxygen and they are under the care of an anesthesia team. But this is a unique situation to acquire difficult-to-reproduce data. To assist further improve the algorithms for what it looks like when someone has an acute overdose.”

For the simulation, the team recruited healthy volunteers undergoing previously scheduled elective procedures. After receiving informed consent, the patients subsequently received normal anesthetic medicines that resulted to 30 seconds of slowed or absent breathing. And these events were documented by the device. The system successfully predicted 19 out of the 20 simulated overdoses. For the one example that was inaccurate, the patient’s respiratory rate was slightly above the algorithm’s threshold.